Villas and the suburban impulse

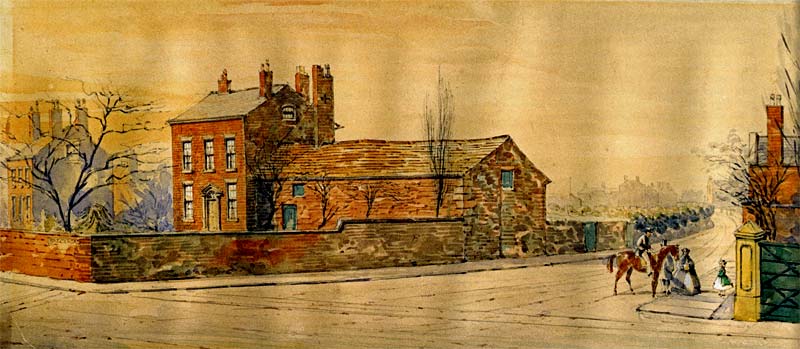

Figure 4 William Herdman 's view of Anfield Road, dated 1861, captures the sylvan setting of many early villas. In the distance gate piers announce the drive to St Ann's Cottage and in the foreground a stable and coach house stand next to the road, facing the tree-lined grounds of Belle Vue House (demolished 1870s).

The stable and coach house are characteristic villa details in the area but Herdman seems to have invented them here to balance his composition. [Liverpool Record Office, Liverpool Libraries, Herdman Collection 178]

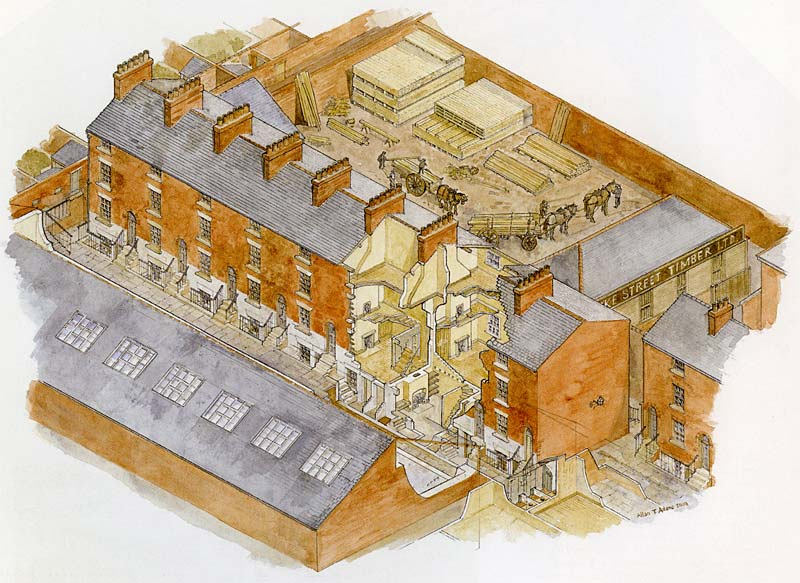

Figure 6 (far right » ») These back-to-back houses forming Duke's Terrace (formerly Bridson's Buildings), Court No 5, Duke Street, were built just a stone's throw from Parr's house (see Fig 5) in 1843. Though hemmed in by a timber yard and a police station they were by no means the worst of their kind; despite having separate external doorways the cellars appear not to have been intended for separate occupation. This reconstruction drawing shows how they would have been occupied in the middle of the 19th century. The three privies (bottom right) served 9 of the 18 houses.

Figure 7 (right ») No 2 Court, Sylvester Street, Liverpool, photographed by Richard Brown in July 1913. By the 1830s just over a third of Liverpool's entire population lived in court housing or cellars. [Liverpool Record Office, Liverpool Libraries 352 HOU 82119]

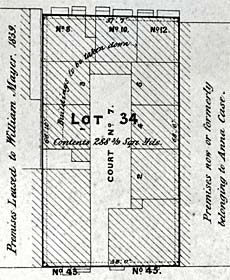

Figure 8 (above) In 1869 Liverpool Corporation sold various properties on condition that the purchaser demolished and did not replace those examples of housing which it considered unfit. The condemned houses were mainly built in narrow courts. In this example - Court No 7 between Parr Street (bottom) and the narrow Back Seel Street (top), only yards from Thomas Parr's house (see Fig 5) - four houses were to be taken down, leaving more space, light and ventilation for the remainder. The houses fronting Back Seel Street have light wells in front of them and may have incorporated cellar dwellings.

[Liverpool Record Office, Liverpool Libraries Hf 333 COR]

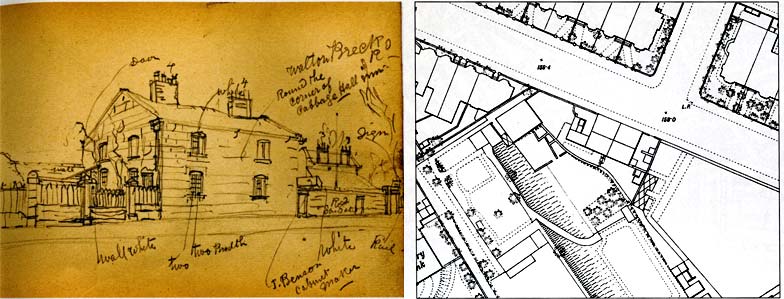

Figure 10 The 1st edition of the Ordnance Survey 6" map, surveyed 1845-9, showing the boundary between Everton (which included Breckfield) and Walton-on-the-Hill (which included Anfield).

The still-rural nature of Anfield and Breckfield contrasts with the increasingly built-up character of Everton. Villa building in Anfield and Breckfield has thus far been concentrated in Cabbage Hall, near the newly built Holy Trinity Church, and along Annfield Lane.

Villas mentioned in the text, and some associated buildings, are numbered:

1 Bronte Cottage

2 Bronte House

3 Elm Bank

4 Woodlands

5 Roseneath Cottage

6 Belle Vue House

7 St Ann's Hill House

8 Annfield House

9 Annfield Cottage

10 Breck House

11 Ash Leigh

12 Broadbent's Cottages

13 Cabbage Hall Inn

14 Post Office

15 Holy Trinity Church

16 Stone Hill Cottage

17 Stone Hill House

18 Spring Bank House

19 Breckfield House

20 Odd House

21 Breckfield Cottage

[Reproduced from the 1851 Ordnance Survey map]

Figure 11 (below) The Cabbage Hall Inn on Breck Road, depicted here in a photograph ofc!865, was a well-known rendezvous when the character of the area was still largely rural. The destination board in the carriage reads 'NECROPOLIS'- a reference to the Liverpool Necropolis, a cemetery on West Derby Road, Everton, a private initiative opened in 1825 and closed in 1898. A large extension to the inn was built in the 1930s and the earlier building was subsequently demolished. [Liverpool Record Office, Liverpool Libraries, Photographs and Small Prints]

Figure 12 (far right » ») This watercolour by William Herdman, dated 1863, shows the junction of Breck Road (passing across the foreground) and Breckfield Road North. Well-spaced small villas line the road to the left; to the right is the main entrance to Breckfield House. The building in the centre, known as the Odd House, was purchased for road widening in 1865 and demolished. (See also inside front cover), [Liverpool Record Office, Liverpool Libraries, Herdman Collection 642]

Figure 13 (above) Bronte House, one of the more opulent villas, as shown on the Everton Tithe Map, 1846. A gate lodge at the junction of Walton Lane and Walton Breck Road marks the start of a long sinuous drive through the landscaped grounds. The house, built c!813, has a south-facing entrance front and a bow-fronted west elevation overlooking a shrubbery and the distant Mersey. To the north lie the stable yard, kitchen garden and what was probably a gardener's cottage. The house was demolished and Bodley, Butterfield, Goldie, Paley and Nesfield Streets, with their small terraced houses, covered the grounds in the late 1870s. [Reproduced with permission of the County Archivist Lancashire Record Office, DRLI1/25]

Figure 16 (above) Small villas were often known in the early 19th century as 'cottage-villas' - cottages for short. Roseneath Cottage, unusual for Anfield in being faced entirely in red sandstone, was home to Mary Nickson in 1847. William Nickson and Thomas Nickson, doubtless relatives, lived at nearby Woodlands and St Ann's Cottage respectively, giving a clannish quality to this exclusive stretch of Anfield Road. [AA045474]

Figure 17 (above) Ash Leigh, a villa development of the 1840s. In the 1851 census 3 of the 12 householders - Gottlieb Beyer, described as a Prussian general merchant; Juncker Philips, a German general commissioning merchant; and John Bincke, a general merchant and hemp broker of Danzig (now Gdansk, Poland) - reflected the cosmopolitan influences of a major seaport. [Reproduced from the 1891 Ordnance Survey map, surveyed 1890]

Figure 19 (right) (a) 9 and 11 St Domingo Grove and (b) the adjoining pair, 13 and 15, have identical plan footprints and massing, but the former is Italianate, distantly recalling the houses of the merchant princes of Renaissance Italy, while the latter is Tudor Gothic, a self-consciously English style. [AA045527,AA045528]

Figure 20 (below) The villas of Anfield Road can be seen in the distance (right) in this detail of a coloured lithograph by John M McGahey depicting the Grand Fancy Fair, Flower Show and Bazaar held in June 1870 at Stanley Park. The event was in aid of the new Stanley Hospital. [Liverpool Record Office, Liverpool Libraries, Binns Collection C113J

Figure 21 (far right » ») Mill Bank, 35-45 Anfield Road, c!860: three pairs of stuccoed villas with Gothic detailing. The residents in 1862 included a timber merchant, a tobacco manufacturer, the manager of the Liverpool & London Insurance Company (see Fig 26), a broker and a merchant. [AA045492]

Figure 22a The size and aspect of the villa plot led to variations in design: (right) at 21 and 23 Anfield Road (1870s) unusual apse-like sculleries are placed on the entrance front in order to keep the more prestigious garden front (overlooking Stanley Park) clear. [AA 045478]

Figure 23 (far right » ») Stanley House, 73 Anfield Road, built for brewer and football promoter John Moulding in 1876, exploits its position overlooking Stanley Park through the form of this tall stair turret on the garden elevation. [DP027855]

Figure 22b (above) 90 and 92 Burleigh Road South (c1870) occupy shallow plots and consequently place services, as well as the entrance, in a side projection. [AA 045546]

Figure 22b (above) 90 and 92 Burleigh Road South (c1870) occupy shallow plots and consequently place services, as well as the entrance, in a side projection. [AA 045546]

Figure 24 (right) (a) Broadbent's Cottages as depicted by Hugh Magenis, 1886-8. Two entrances can be made out in the left-hand gable and there must have been another two on the opposite end. Most back-to-backs were built in longer rows; 'clusters' of just four, where each house has two external walls, are better ventilated. Hugh Magenis sketched the cottages at a time when the area was changing rapidly, but they survived until at least 1911 (see also Fig 78). [Liverpool Record Office, Liverpool Libraries Hq 741.91 MAG]; (b) the cottages (the square block of four fronting the road at the T-junction) as shown on the Ordnance Survey map of 1891, surveyed 1890.

Twin forces of repulsion and attraction propel people from town to suburb. These forces, which have varied in intensity over time and from place to place, have their origin in much wider patterns of thought and feeling contrasting the relative merits of town and country, in which the suburb occupies a middle ground seeking to maximise the advantages, and minimise the drawbacks, of both - blending the best of nature and society (Fig 4).

Twin forces of repulsion and attraction propel people from town to suburb. These forces, which have varied in intensity over time and from place to place, have their origin in much wider patterns of thought and feeling contrasting the relative merits of town and country, in which the suburb occupies a middle ground seeking to maximise the advantages, and minimise the drawbacks, of both - blending the best of nature and society (Fig 4). In 18th-century towns the houses of the better off - professional men, merchants, wealthier tradesmen and their families - tended to line the main thoroughfares. While some individuals built houses on the outskirts of town, many remained in the central areas, close to their place of business (Fig 5). Poorer housing either lined the lesser thoroughfares, which were typically narrower and less favourably situated, or developed in the courts behind thoroughfare houses and inns. Many houses in courts were built as 'blind-backs' against the wall of the neighbouring court or were placed back-to-back with other houses, arrangements which considerably diminished light and ventilation (Fig 6). Liverpool's many thousands of cellar dwellings suffered from similar defects. Sanitary provision was meagre and often squalid. As the population rose, houses whose position might once have been attractive were tainted by the proximity of poorer-quality dwellings, and courts became ever more densely inhabited (Fig 7). Even by contemporary standards Liverpool's problems were severe enough for it to be dubbed 'the most unhealthy town in England' in the early 1840s, with a mean life expectancy of just 26 years. The response was vigorous.

In 18th-century towns the houses of the better off - professional men, merchants, wealthier tradesmen and their families - tended to line the main thoroughfares. While some individuals built houses on the outskirts of town, many remained in the central areas, close to their place of business (Fig 5). Poorer housing either lined the lesser thoroughfares, which were typically narrower and less favourably situated, or developed in the courts behind thoroughfare houses and inns. Many houses in courts were built as 'blind-backs' against the wall of the neighbouring court or were placed back-to-back with other houses, arrangements which considerably diminished light and ventilation (Fig 6). Liverpool's many thousands of cellar dwellings suffered from similar defects. Sanitary provision was meagre and often squalid. As the population rose, houses whose position might once have been attractive were tainted by the proximity of poorer-quality dwellings, and courts became ever more densely inhabited (Fig 7). Even by contemporary standards Liverpool's problems were severe enough for it to be dubbed 'the most unhealthy town in England' in the early 1840s, with a mean life expectancy of just 26 years. The response was vigorous. A Building Act was secured in 1842, allowing the Corporation to enforce basic standards for housing, and the 1846 Liverpool Sanitary Act, conferring among other things the power to close the worst cellar dwellings, paved the way for the appointment of the country's first Medical Officer of Health the following year. Shortly afterwards Liverpool Corporation began buying up slum property and selling it on condition that the worst housing was demolished (Fig 8).

A Building Act was secured in 1842, allowing the Corporation to enforce basic standards for housing, and the 1846 Liverpool Sanitary Act, conferring among other things the power to close the worst cellar dwellings, paved the way for the appointment of the country's first Medical Officer of Health the following year. Shortly afterwards Liverpool Corporation began buying up slum property and selling it on condition that the worst housing was demolished (Fig 8).It was to be many years, however, before real advances were achieved by such measures; in the short term overcrowding actually increased in some areas since it proved easier to close cellars than to induce builders to provide homes to the new standard. In the meantime 19th-century towns, despite the economic and cultural opportunities which they undeniably presented, became increasingly associated in the public mind with overcrowding, disease, pollution, crime and immorality. Recurrent epidemics of typhus and cholera were especially feared, and Liverpool suffered severely in 1847 and 1849 as victims of the Irish famine crowded into cellars and common lodging houses. In tempting contrast the suburbs offered a safer, healthier and more spacious environment better suited to family life, albeit at the cost of a longer journey to one's place of work.

One of the privileges of wealth has long been the freedom to allocate one house to business and another to pleasure. It was exercised long before the widespread adoption of the term 'villa' in early 18th-century England but thereafter the practice grew rapidly in popularity. Some relinquished their town residence altogether, centring family life in the suburbs and decisively separating the realms of work and domesticity (though associates might continue to be entertained in the family home as a way of cementing business relationships). For Liverpool merchants a favoured location for villas was Everton Brow. Perched high above the Mersey and its shipping, these houses enjoyed ample grounds and semi-rural surroundings, yet by horse and carriage they were within a few minutes of the docks and counting houses of central Liverpool. A 19th-century writer, recalling the appearance of the area around 1825, drew this picture:

One of the privileges of wealth has long been the freedom to allocate one house to business and another to pleasure. It was exercised long before the widespread adoption of the term 'villa' in early 18th-century England but thereafter the practice grew rapidly in popularity. Some relinquished their town residence altogether, centring family life in the suburbs and decisively separating the realms of work and domesticity (though associates might continue to be entertained in the family home as a way of cementing business relationships). For Liverpool merchants a favoured location for villas was Everton Brow. Perched high above the Mersey and its shipping, these houses enjoyed ample grounds and semi-rural surroundings, yet by horse and carriage they were within a few minutes of the docks and counting houses of central Liverpool. A 19th-century writer, recalling the appearance of the area around 1825, drew this picture:The crown of the hill and its western slope were sufficiently built on to take away the appearance of baldness or nakedness, and yet not so densely as to crowd it inconveniently. From the umbrageous foliage of their gardens and pleasure-grounds, noble mansions, in tier above tier, looked out on a lovely landscape.

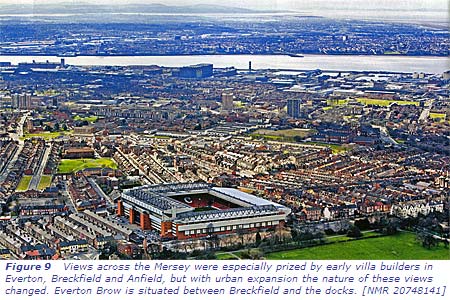

Inevitably the best sites for villas were quickly taken and what was once select became more crowded, though still genteel. Prospective builders began to look further afield and by the end of the 18th century the first villas had appeared in Anfield and Breckfield. Though less well placed than Everton for views across the Mersey the area was similarly elevated and was only a little further removed from the city centre (Fig 9).

Inevitably the best sites for villas were quickly taken and what was once select became more crowded, though still genteel. Prospective builders began to look further afield and by the end of the 18th century the first villas had appeared in Anfield and Breckfield. Though less well placed than Everton for views across the Mersey the area was similarly elevated and was only a little further removed from the city centre (Fig 9).Although they now merge seamlessly, Anfield and Breckfield were originally administratively distinct. Breckfield lay within Everton township, which was formally absorbed by the town of Liverpool in 1835, whereas Anfield formed part of Walton-on-the-Hill, which did not become part of Liverpool until 1895 (Fig 10). But both were on the periphery of their mother settlement (the name Walton Breck was often applied to an area straddling the boundary) and although the ancient administrative distinction remains fossilised in the modern ward boundary and the roads which overlie it, it had little impact on development: Anfield and Breckfield evolved at much the same time and in similar ways.

In the early 19th century only a handful of roads criss-crossed the area and the villas, congregating along those roads which offered an elevated outlook, stood in what was otherwise an almost entirely rural landscape, with here and there a quarry of red sandstone supplying building materials, and a solitary windmill on Anfield Road (then known as Annfield Lane). A small group of houses clustered around the long-established Cabbage Hall Inn (Fig 11), which gave its name to the immediate locality - reputedly 'the very Arcadia of Liverpool', and the object of 'rural excursions... by the lower and middle orders'.

None of the earliest villas in Anfield and Breckfield - those built in the late 18th and early 19th centuries - survives, but we know the names and trades of many of their occupants, whilst maps, and occasionally historic views, tell us something of their architectural character and grounds. Breckfield House, at the junction of Breck Road and Breckfield Road North, was home in the late 18th century to George Case, Mayor of Liverpool (Fig 12). Bronte House (Fig 13), between Walton Lane and Sleepers Hill, was built around 1813 for the merchant Samuel Woodhouse, and was named after Bronte in Sicily (Horatio Nelson was made Duke of Bronte in 1799 for assisting Ferdinand III, King of Naples, in suppressing an insurrection). Anfield Road, then a country lane lined with hedges and hedgerow trees, was especially favoured. Perhaps the best sites were those towards the north-western end where Belle Vue House looked south-westwards towards the Mersey, but others to the south-east, such as St Ann's Hill House and Annfield House, enjoyed a pleasantly rural garden outlook to the north-east.

None of the earliest villas in Anfield and Breckfield - those built in the late 18th and early 19th centuries - survives, but we know the names and trades of many of their occupants, whilst maps, and occasionally historic views, tell us something of their architectural character and grounds. Breckfield House, at the junction of Breck Road and Breckfield Road North, was home in the late 18th century to George Case, Mayor of Liverpool (Fig 12). Bronte House (Fig 13), between Walton Lane and Sleepers Hill, was built around 1813 for the merchant Samuel Woodhouse, and was named after Bronte in Sicily (Horatio Nelson was made Duke of Bronte in 1799 for assisting Ferdinand III, King of Naples, in suppressing an insurrection). Anfield Road, then a country lane lined with hedges and hedgerow trees, was especially favoured. Perhaps the best sites were those towards the north-western end where Belle Vue House looked south-westwards towards the Mersey, but others to the south-east, such as St Ann's Hill House and Annfield House, enjoyed a pleasantly rural garden outlook to the north-east. The trend of the field boundaries was generally from south-west to north-east, at right-angles to the contours of the gently undulating ground. Only the largest villas, such as Bronte House and Annfield House, had grounds extensive enough to encompass a whole field, and where they did a part might be cropped as meadow, as happened at Belle Vue House in the 1840s. More often villas occupied just a corner of a field, but in either case they respected the existing field system, inaugurating a process which ultimately saw these boundaries perpetuated in the modern street pattern (compare Figs 10 and 25). Some of the names of these fields have endured to the present day. Anfield takes its name from the Hangfields, narrow strips running back inland from a brow overlooking the Mersey. Sleepers Hill has its origin in Great and Little Sleepers, two areas of former common land, while the 'Breck' in Breckfield probably refers to an area of uncultivated land.

The trend of the field boundaries was generally from south-west to north-east, at right-angles to the contours of the gently undulating ground. Only the largest villas, such as Bronte House and Annfield House, had grounds extensive enough to encompass a whole field, and where they did a part might be cropped as meadow, as happened at Belle Vue House in the 1840s. More often villas occupied just a corner of a field, but in either case they respected the existing field system, inaugurating a process which ultimately saw these boundaries perpetuated in the modern street pattern (compare Figs 10 and 25). Some of the names of these fields have endured to the present day. Anfield takes its name from the Hangfields, narrow strips running back inland from a brow overlooking the Mersey. Sleepers Hill has its origin in Great and Little Sleepers, two areas of former common land, while the 'Breck' in Breckfield probably refers to an area of uncultivated land. The earliest surviving villas date from the years immediately after 1840. By this time Everton was beginning to fill up with lower-grade housing attracted by the northwards spread of Liverpool's docks, and as attention shifted to newly desirable Anfield and Breckfield the pace of villa building there quickened. The earliest surviving villa on Anfield Road is Woodlands, a stuccoed Italianate house now hemmed in on two sides by later extensions (Fig 14). A substantial detached villa in generous grounds, it was the home in the 1860s of Henry Tate (1819-99), later famous both for his sugar-refining business and as the first benefactor of London's Tate Gallery, who moved here after a number of years living at nearby Belle Vue House.

The earliest surviving villas date from the years immediately after 1840. By this time Everton was beginning to fill up with lower-grade housing attracted by the northwards spread of Liverpool's docks, and as attention shifted to newly desirable Anfield and Breckfield the pace of villa building there quickened. The earliest surviving villa on Anfield Road is Woodlands, a stuccoed Italianate house now hemmed in on two sides by later extensions (Fig 14). A substantial detached villa in generous grounds, it was the home in the 1860s of Henry Tate (1819-99), later famous both for his sugar-refining business and as the first benefactor of London's Tate Gallery, who moved here after a number of years living at nearby Belle Vue House. The names given to these early villas, and often proclaimed on elaborate stone gate piers (Fig 15), are particularly revealing. The very use of names was laden with social pretension: in Liverpool, where street numbering was well established in the central district by 1800, a named address conferred a social distinction on the occupants. Some villas were called 'lodges', a label often adopted for the secondary seats of the gentry and aristocracy, while others bore names (like Spring Bank House) which evoked their pastoral or sylvan setting. The term 'cottage' expressed a particular yearning for the simple pleasures of country life. Although these cottages were mostly among the smaller villas they should not be confused with the cramped and often insanitary homes of rural labourers, to which they are only distantly and whimsically related.

The names given to these early villas, and often proclaimed on elaborate stone gate piers (Fig 15), are particularly revealing. The very use of names was laden with social pretension: in Liverpool, where street numbering was well established in the central district by 1800, a named address conferred a social distinction on the occupants. Some villas were called 'lodges', a label often adopted for the secondary seats of the gentry and aristocracy, while others bore names (like Spring Bank House) which evoked their pastoral or sylvan setting. The term 'cottage' expressed a particular yearning for the simple pleasures of country life. Although these cottages were mostly among the smaller villas they should not be confused with the cramped and often insanitary homes of rural labourers, to which they are only distantly and whimsically related.

They were more directly influenced by the popularity of the cottage orné style, which emphasised a rarefied notion of picturesque rusticity, usually in parkland settings. Half a dozen or so can be identified in Anfield and Breckfield, and of this number four (Annfield Cottage, Bronte Cottage, Breckfield Cottage and Stone Hill Cottage) share the same name as a larger villa alongside, suggesting that their origins - and perhaps their households - were related. Roseneath Cottage, Anfield Road, is a rare survivor (Fig 16). Built in the local red sandstone it differs from the larger villas nearby in being built hard against the roadside, where it had an attached stable and coach house.

They were more directly influenced by the popularity of the cottage orné style, which emphasised a rarefied notion of picturesque rusticity, usually in parkland settings. Half a dozen or so can be identified in Anfield and Breckfield, and of this number four (Annfield Cottage, Bronte Cottage, Breckfield Cottage and Stone Hill Cottage) share the same name as a larger villa alongside, suggesting that their origins - and perhaps their households - were related. Roseneath Cottage, Anfield Road, is a rare survivor (Fig 16). Built in the local red sandstone it differs from the larger villas nearby in being built hard against the roadside, where it had an attached stable and coach house.Two important new villa developments of the 1840s were the building of Ash Leigh (Fig 17), a short cul-de-sac off Walton Breck Road, and the laying out of St Domingo Grove (Fig 18), a long tree-lined avenue opening off Breckfield Road North and initially closed at the other end. Where previously the villas had been built singly and styled idiosyncratically on scattered plots of widely varying size, these were systematic and more intensive developments undertaken on a substantial scale by one or more speculative builders. The development of Ash Leigh was completed before 1847 and swept away in the 20th century.

Figure 18 By contrast with Ash Leigh, the development of St Domingo Grove no sooner started than it stalled. In this watercolour, by James Innes Herdman, the grounds of one of the first houses in St Domingo Grove are visible on the extreme right but the Grove is otherwise still a field - the meagre trees may be the beginnings of the intended avenue. The distant church is probably Queen's Road Presbyterian Church, 1861. This was the view from West Villa, 41 St Domingo Vale, the home of the artist's father, William Gawin Herdman, from 1855. [Liverpool Record Office, Liverpool Libraries, Herdman Collection 1479]

In St Domingo Grove construction commenced before 1846 but promptly stalled: in 1851 two houses were occupied, one by a merchant and one by the Secretary to the Liverpool Dispensary, but a further two stood empty, casualties of a housing market that was volatile, highly competitive and socially fine-tuned. Work did not resume in earnest until the early 1860s, suggesting weak demand for these houses. Faster progress was achieved on a parallel street, St Domingo Vale, where somewhat smaller villas found a readier market from the mid-1850s. The houses in both streets were more regimented than those in Ash Leigh, built in 'semi-detached' pairs with a common building line, a broad uniformity of scale and a limited range of styles and plan-forms (Fig 19).

The increasing standardisation and diminishing stature of these houses herald the arrival in Anfield and Breckfield of a less wealthy stratum of society. But even as they were being built the downward social trend was continuing apace and neither St Domingo Grove nor St Domingo Vale was completed as planned. In their place came successive waves of terraced housing, breaking first on Breckfield's southern margins and sweeping steadily northwards.

By the late 1860s villa building in Breckfield had ceased but in the most select part of Anfield, along Anfield Road, it continued for another decade. This was the part of the area most distant from central Liverpool, and its eligibility as a location for villa building was prolonged by the opening of Stanley Park in 1870 (Fig 20).The park's grounds were landscaped by Edward Kemp (1817-91), who learnt his trade at Chatsworth House, Derbyshire, with Joseph Paxton (with whom he subsequently worked on Birkenhead Park, 1843-7), and the buildings were designed by the Borough Surveyor, E R Robson (1835-1917), later a distinguished schools architect in London. Although the park, which stretched as far as Walton-on-the-Hill to the west and Anfield Cemetery to the north, was explicitly dedicated to the recreation of working people it had the possibly unintended consequence of guaranteeing the outlook of houses on the north-east side of Anfield Road at a time when cherished views elsewhere were succumbing to new housing.

By the late 1860s villa building in Breckfield had ceased but in the most select part of Anfield, along Anfield Road, it continued for another decade. This was the part of the area most distant from central Liverpool, and its eligibility as a location for villa building was prolonged by the opening of Stanley Park in 1870 (Fig 20).The park's grounds were landscaped by Edward Kemp (1817-91), who learnt his trade at Chatsworth House, Derbyshire, with Joseph Paxton (with whom he subsequently worked on Birkenhead Park, 1843-7), and the buildings were designed by the Borough Surveyor, E R Robson (1835-1917), later a distinguished schools architect in London. Although the park, which stretched as far as Walton-on-the-Hill to the west and Anfield Cemetery to the north, was explicitly dedicated to the recreation of working people it had the possibly unintended consequence of guaranteeing the outlook of houses on the north-east side of Anfield Road at a time when cherished views elsewhere were succumbing to new housing. During the 1850s, 1860s and 1870s the remaining plots bordering the north-east side of Anfield Road were built upon. Paired villas duly made their appearance (Fig 21) and a handful of them were as modest in size as those in St Domingo Vale. Generally, however, a more generous scale prevailed and the houses, even when paired, were more individually styled. Two pairs (21 and 23, 25 and 27), dating from the 1870s, responded in an unusual way to the proximity of Stanley Park by disguising small sculleries as chapel-like apses on the street elevation of the house so as not to clutter the more prestigious rear elevation towards the garden and park (Fig 22). One of the last of the villas, Stanley House, built in 1876 for John Moulding, brewer and football promoter, is as brash as any in the area and also one of the best preserved externally. Here too the value of the outlook towards the north-east is emphasised in the form of a tall, well-lit stair turret rising on the garden elevation, while towards the street a stable and coach-house block is set to one side of a large forecourt (Fig 23; see also Fig 55).

During the 1850s, 1860s and 1870s the remaining plots bordering the north-east side of Anfield Road were built upon. Paired villas duly made their appearance (Fig 21) and a handful of them were as modest in size as those in St Domingo Vale. Generally, however, a more generous scale prevailed and the houses, even when paired, were more individually styled. Two pairs (21 and 23, 25 and 27), dating from the 1870s, responded in an unusual way to the proximity of Stanley Park by disguising small sculleries as chapel-like apses on the street elevation of the house so as not to clutter the more prestigious rear elevation towards the garden and park (Fig 22). One of the last of the villas, Stanley House, built in 1876 for John Moulding, brewer and football promoter, is as brash as any in the area and also one of the best preserved externally. Here too the value of the outlook towards the north-east is emphasised in the form of a tall, well-lit stair turret rising on the garden elevation, while towards the street a stable and coach-house block is set to one side of a large forecourt (Fig 23; see also Fig 55). The occupants of these villas, on the whole, were not the cream of Liverpool's mercantile elite - Henry Tate, for example, moved further out to Allerton Beeches (1883-4), a house designed for him by high-flying architect Norman Shaw, as his wealth increased - but they were men of substantial means, including bankers, merchants, manufacturers, brokers and managers, and by the standards of the day they lived comfortably. In 1851 the banker George Arkles, who lived at Annfield House, had a household of seven tended by three domestic servants; the grounds were looked after by a gardener who lived with his family in a separate cottage, and a coachman and his family occupied the gate-lodge.

Few villas enjoyed the luxury of a gate-lodge but several of the larger ones, including St Ann's Hill House and Belle Vue House, had separate accommodation for a gardener or had either a coachman or a groom among their resident servants. James Moon, a retired merchant who had taken Bronte House, was unusual in having a butler.

The occupants of these villas, on the whole, were not the cream of Liverpool's mercantile elite - Henry Tate, for example, moved further out to Allerton Beeches (1883-4), a house designed for him by high-flying architect Norman Shaw, as his wealth increased - but they were men of substantial means, including bankers, merchants, manufacturers, brokers and managers, and by the standards of the day they lived comfortably. In 1851 the banker George Arkles, who lived at Annfield House, had a household of seven tended by three domestic servants; the grounds were looked after by a gardener who lived with his family in a separate cottage, and a coachman and his family occupied the gate-lodge.

Few villas enjoyed the luxury of a gate-lodge but several of the larger ones, including St Ann's Hill House and Belle Vue House, had separate accommodation for a gardener or had either a coachman or a groom among their resident servants. James Moon, a retired merchant who had taken Bronte House, was unusual in having a butler. The occurrence of grooms and coachmen in the census returns is a reminder of the importance of the horse in this relatively far-flung suburb. Before the 1860s there were few facilities in Anfield and Breckfield for the use of the villa-dwellers. They were a well-off, thinly spread and relatively mobile population, who could count on the assiduous attentions of tradesmen based outside the locality, soliciting business and delivering orders. There was no need, consequently, for neighbourhood shops. The few facilities which the area afforded in the 1840s included the long-established Cabbage Hall Inn and the nearby Post Office. For everything else a visit to town, or to a more populous suburb such as Everton, was required.

The occurrence of grooms and coachmen in the census returns is a reminder of the importance of the horse in this relatively far-flung suburb. Before the 1860s there were few facilities in Anfield and Breckfield for the use of the villa-dwellers. They were a well-off, thinly spread and relatively mobile population, who could count on the assiduous attentions of tradesmen based outside the locality, soliciting business and delivering orders. There was no need, consequently, for neighbourhood shops. The few facilities which the area afforded in the 1840s included the long-established Cabbage Hall Inn and the nearby Post Office. For everything else a visit to town, or to a more populous suburb such as Everton, was required.There were also a few individuals who evidently worked for the villa-dwellers but were not found accommodation by them. Broadbent's Cottages stood on Walton Breck Road on the rear of the property belonging to the Cabbage Hall Inn (proprietor John Broadbent in 1835). Here in 1851 lived a liveryman, a gardener's assistant and his laundress wife, and another laundress who was married to a shoemaker. Map and directory evidence confirms that there were four cottages, not three, and that they were arranged back-to-back (Fig 24; see also Fig 78). The Liverpool building by-laws discouraged the building of back-to-backs but they did not ban them explicitly until 1861; in any case the by-laws did not apply to Walton-on-the-Hill township, where these cottages were situated, until 1895.

« Previous Top Home Next »